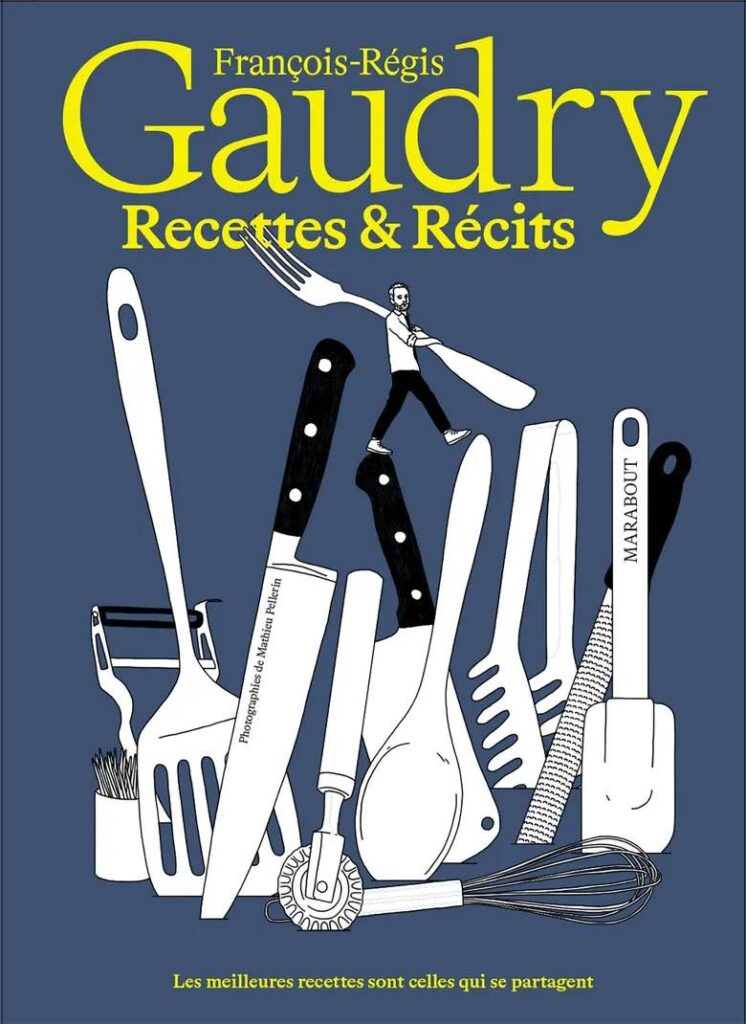

At the end of last year, he published a new book: Recettes & Récits. A collection of his 155 ultimate recipes. What’s more, on 12 February, François-Régis Gaudry will be in Beaune to discuss this highly personal work. Here’s a sneak preview…

This book doesn’t come out of the blue: as you say in its preface, you’ve always cooked…

My wife loves to cook, but she’s given up a bit. I love going to the market every Saturday morning, imagining on the way what I’m going to prepare, choosing my ingredients… And then, often, at home, cooking is a form of language, a way of paying special attention to one’s children, two daughters in this case, whom I haven’t always seen enough of because of my work. This nurturing role is undoubtedly the way I’ve found to make up for it. In fact, this is above all a family cuisine, with no technical ambitions. It’s the opposite of a challenge or a show. By nature, I’m in a bit of a hurry. So my recipes are made in 2 or 3 steps. For example, I’ve never launched into a pâté en croûte or a Paris-Brest, although as a food journalist I admire the patience it takes to make them. No, I’m more interested in the relationship between efficiency and emotion. How can you not spend hours and touch your friends?

However, this book comes rather late, after quite a few others. You mention a certain restraint…

Yes, because of a little complex: the impostor syndrome. I’d always cooked by instinct, like my mother, Denise, and my grandmother, Mamyta. I’d never written down a single recipe. For the purposes of my posts on social networks and my broadcasts on France Inter, I had to start. But I had my doubts: would people be interested? In the end I convinced myself that my recipes had the advantage of being simple. Basically, I like the idea of perfectly executed basics: a caponata or a caramelised pork dish executed by the book, but without the twist of the chef I’m not.

Doesn’t the age also lend itself more to a collection of simple, heritage and personal recipes?

I think so. I’ve always cooked like that. But I can see it in some of the restaurants I’ve visited recently, like Frédéric Anton’s La Ferme du Pré, or Gilles Goujon’s Micheline: if this simple cuisine has never disappeared, today more than ever, it’s reassuring. Blanquette, boeuf bourguignon and steak au poivre are all making a comeback. In these troubled times, we need these reference points, these milestones of identity, to comfort and repair us.

As you write in Recettes & Récits, cooking is all about the people who pass the torch. Who are yours?

I’ve noticed, although it wasn’t planned, that there are more women here than men. That’s no coincidence. I’m very interested in this type of cuisine. It reminds me of the way my mother and grandmother used to cook. They were my first two teachers. Later, others joined them, starting with Suzy Palatin, who was just as talented at making boeuf bourguignon, Italian-style pasta or Tom kha kai, a coconut milk soup with lemongrass and chicken, the recipe for which I borrowed from her. And for good reason: I’ve never eaten any as good as her. She has a flair for cooking, the right intuitions, the right gestures… Not everyone can do that. I often say of my models that they cook like they breathe. Suzy Palatin is obviously like that, as is Andrée Zana Murat. Alongside this, I’m also very attached to the family dishes of quite a few of my chef friends, like Emmanuel Renaut’s tartiflette. He’s a technician par excellence, but I’m more interested in his domestic heritage, his secret garden. Another typical example is Anne-Sophie Pic’s mother’s tarragon chicken, one of her favourite recipes, long reserved for the private sphere.

You have taken care to pay tribute to each of these models, through the little story behind the recipe you borrowed from them…

These stories are as important to me as the dishes themselves. When I go to a friend’s house for dinner and love one of their dishes, my first instinct is to ask where the recipe comes from. That’s what excites me and, without wishing to lecture anyone, what often frustrates me about cookery books published today: the lack of narrative and, in the end, the impression of holding a catalogue of recipes in my hands. Beyond this curiosity, I felt it necessary to quote my sources. It’s the least I can do. I wanted to pay tribute to those who have nourished me.

In fact, it’s these people who guide the chaptering of this book, between family legacies, encounters during your trips, great chefs… Where one might have expected a book organised by season…

That’s true. There’s only one seasonal repertoire that I really wanted to focus on: summer. It’s a time when I cook a lot, for a lot of people, often unexpectedly. Something that doesn’t happen in real life the rest of the time. Every year, for 6 weeks, we entertain in a slightly unbridled way, every evening. That’s what I enjoy.

So did we when we read this chapter. Especially as you clearly state on the back cover: your recipes are impossible to spoil. How can that be?

They don’t come out of the blue. I try them out very, very often. As Alain Passard would say, I’ve polished the gesture. For each of them, I now know exactly what it should look like at what moment.

Another touching fact is that, thanks to this book, the reader is really transported to your home…

These are my kitchen, my casseroles, my plates… that have been photographed. There are very few external additions. I wanted to convey the truth of the preparations as I serve them at home. And it doesn’t matter if, for example, the edges of the gratin dish are a little blackened in the picture. That’s how it comes out of the oven at home. That’s how my mother and grandmother made it.

As well as your recipes, this book presents their history and your little tips, but not only that… It also talks about your culinary library, your spices from all around the world, your oils and vinegars, your knives and… your wines: what kind of drinker are you?

In this area, I remain very modest. I’m not a specialist. I have too much respect for the great connoisseurs around me, like Jérôme Gagnez, who provide me with ongoing training in this particular subject. The result? I know more about wine than I did fifteen years ago, and probably less than I will in another fifteen years. Because I’m getting caught up in the game, particularly by meeting more and more winemakers. It’s an important part of my approach to wine. In fact, in the small selection I made for this book, I only chose cuvées from winemakers who are friends. I need to put a face on a bottle. So I drink an intention, a landscape…