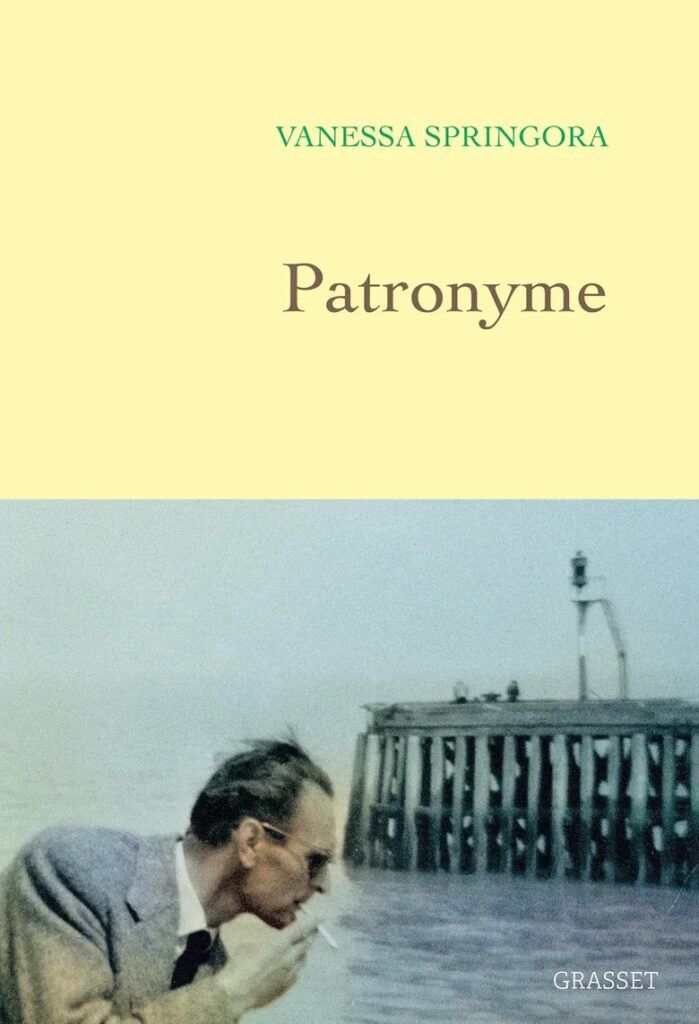

In the days following the publication of her first book, ‘Consent’, Vanessa Springora learns of the sudden death of her father, after decades of absence. When she was clearing out her flat, she discovered two photos of her paternal grandfather wearing Nazi insignia. She was appalled. A kaleidoscopic investigation ensued: the common thread running through her new book ‘Patronyme’. Here’s a sneak preview, before she comes to Athenaeum on 3 April.

After the shock of your discoveries, you put it all aside. Two years later, however, you decide to investigate. But why? What prompted you to take the plunge?

At the time I made these terrifying discoveries in my father’s flat, both about his own life and about my grandfather’s hidden past, I had neither the time nor the inclination to investigate: I was in the middle of releasing ‘Consent’, caught up in a media whirlwind, but also very moved by the opening of the judicial enquiry that the publication of this book entailed. A lot of things happened in quick succession, until the Covid lockdown. It really wasn’t the right time to be dealing with these discoveries. I already had too much to do and think about with ‘Consent’, which was subsequently translated into around thirty languages, extending the promotional period by two years. In the end, what brought me back to these discoveries were two consecutive but unrelated events. First, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and then an almost simultaneous invitation to the Prague Book Festival. As my paternal grandfather was born in Czechoslovakia, I saw this invitation, and the return of war to European soil, as a sign, a kind of moral obligation, not only to my father but also to myself, to look into my grandfather’s troubled past and our Slavic origins.

What made you want, or perhaps need, to write a book about it? This investigation, written for the most part in the first person, in the style of a diary, is very personal. Why did you think that it might be of interest to a wider audience than just your own circle of friends, and what’s more, in this day and age?

I sincerely believe that individual stories all have a universal dimension. Firstly, there is the question of the unspoken, the family taboo around a falsified name and story. All families have secrets, but what interested me above all was understanding the effects of a family secret on subsequent generations. Then, when I discovered my grandfather’s Nazi past, I very quickly felt the need, not to say the duty, to pass on this story. It raises questions that are so topical today: what does each generation carry and pass on? What does it try to hide? The parallels that emerge between the 1930s and the present day are frightening, even more so today when, unfortunately, I see my worst fears being confirmed. This echo of the present with the period leading up to the Second World War convinced me that this was the subject of my next book. Does the past shed light on the present? Is it an eternal restart? I still have faith in literature, I believe it helps us to shed light on our lives, to act as a counterweight, to try to reverse the course of the world… And if we don’t want to make the same mistakes as our elders, we have to start by remembering what they went through, recounting the tragic choices they had to make. In ‘Patronyme’, I also ask myself a lot about the consent to barbarism of ordinary men, like my grandfather. Why and how do we allow ourselves to be seduced by an ideology of hatred? ‘Patronyme’ is therefore also a diary of the years we have just lived through, an attempt to decipher our times, as much as a strictly personal investigation.

With all the information you have gathered, you can reconstruct the broad outline of your grandfather’s life. Your writing style follows, becoming more precise as the investigation progresses…

Yes, it’s writing as close as possible to this investigation in which I involve the readers, so that they can unravel with me the threads of this tangle of far-fetched and contradictory stories, so that they too will want to put the puzzle back together. I had to be very clear and precise so as not to lose them along the way. To make the story even more vivid, I also allowed myself a few short fictional chapters that I wrote in an attempt to fill in the grey areas and reconstruct certain missing links, but always based on factual elements that I was able to unearth. I did a lot of work on archives of all kinds, French, German, Czech and American. I had to turn them into literary material, make them speak in the truest sense of the word. The book is also a literary stroll in the company of authors who mean a lot to me, from Kafka to Kundera, via Jiří Weil and Jaroslav Hašek, Czech authors who bridge the gap between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, not forgetting Zweig, of course, who is central. The book is rather unclassifiable, because nothing was linear in this story of successive breaks and ruptures, both memorial and genealogical, but also geographical and political. I spent a long time looking for the form that would give it unity, while not trying to confine my father and grandfather in portraits that were too rigid or unambiguous. This hybrid construction, in perpetual motion, reflects my hesitations, the obstacles I encountered and the joy of finding answers, however fragmentary. In the end, it’s as elusive as those two male figures who shaped my identity, my father and my grandfather. But, for me, it was the only way to do justice to the complexity of the times and the individuals.

How do you feel after all these months of investigating and writing? What was the price of truth this time?

Even if the results of this investigation seriously dent the image I had of my grandfather, I feel a kind of relief. Painful though they were, I finally got some answers to help me understand the enigma that my father had always been for me, his indecipherable personality, the fact that he had failed to ‘be a father’, precisely, and that he had shirked his responsibilities and any form of commitment, professional or emotional, all his life. I realised that when you don’t question the veracity of an official story, even when it’s clearly truncated or even a lie, you start to take responsibility for the lie yourself. You become an accomplice. And you’re ashamed of it for the rest of your life. That was the case with my father, who always protected his own father’s secret by becoming a mythomaniac. If he invented multiple personalities, prestigious ancestries and positions throughout his life, it was both to cover up his father’s original lie about his true identity and to escape this unmentionable origin. It’s a mechanism that seems obvious to me today, and I’ve seen just how deadly it is. I’m also pleased to have been able to clear the way a little for my son, who now knows more about his origins than I did at his age.